Thug Life (2025) arrived on the heels of enormous hype — fuelled by a glittering announcement trailer, back-2-back promotional appearances by its stars all over the country, controversies over whether Kannada language came from Tamil and a debate over whether Dhee’s or Chinmayi’s rendition of “Mutha Mazhai” was superior.

Early footage hinted at a gripping father–son drama, but the film’s momentum sputtered badly once the story shifted to present day.

1. Miscast or Misused Hero

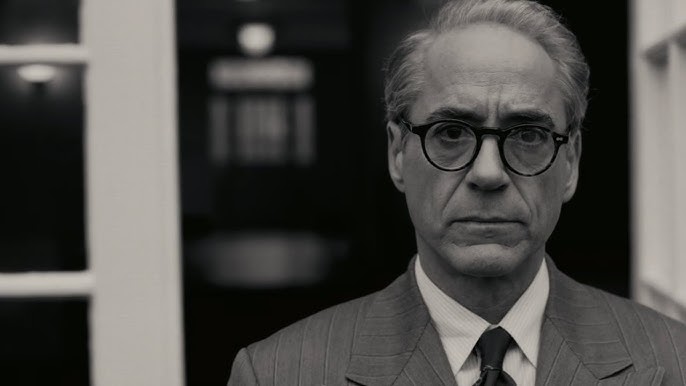

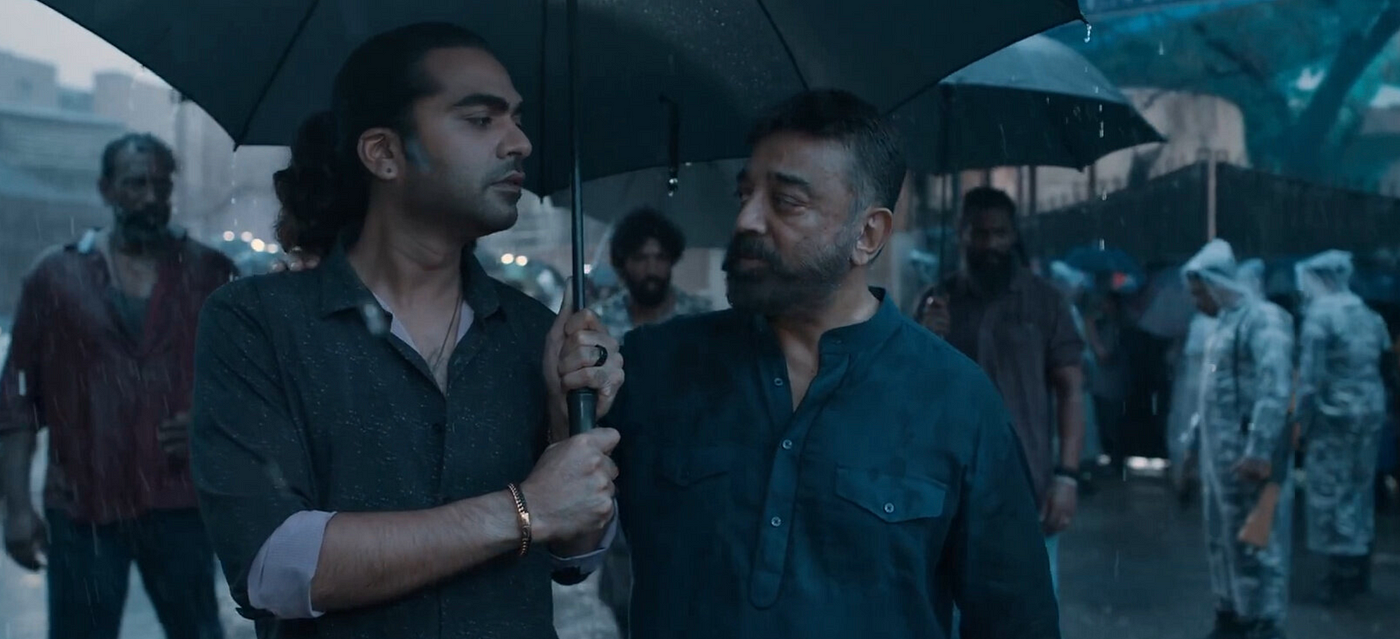

In the flashback sequences, Rangaraja Sakthivel (played by Kamal Haasan) makes a stylish, almost mythic entrance — black‐and‐white cinematography, cool shades, top notch de-aging and a confident bearing that recall his unforgettable truth‐to‐power performance in Nayakan (1987). Yet once the palette shifts to colour, this older Sakthivel speaks and behaves like a frail elder.

At the start, we meet Sakthivel as an aging syndicate boss who boasts that he doesn’t just survive death — he defeats it every time. After supposedly spending less than two years training in Nepal, after the betrayal — after the fall from the cliff with bullet in his body, he returns, having mastered martial arts in his twilight years and immediately dispatches one underling after another in brutal hand‐to‐hand combat. Seeing a septuagenarian transform overnight into a martial‐arts prodigy feels wildly implausible — and, for today’s audiences, downright cringe. A similar disconnect felt in Indian 2 (2024).

2. Awkward Subplot with Indhrani

When Sakthivel’s search for his found-son Amaran’s missing sister leads him to a brothel, the introduction of Indhrani (played by Trisha Krishnan), a strip‐dance performer, should have added emotional depth or suspense. Instead, it lands flat — and frankly awkwardly — because the film does not clarify whether Indhrani is the missing sister in the beginning; this red herring does not fit well. That narrative ambiguity might have worked if handled with subtlety, but here it only jolts the audience out of the story. For a brief moment, the real sister Chandra (played by Aishwarya Lekshmi) appears on screen — and her presence instantly outshines the awkward stripper–turned–love interest for Father and stepson.

3. Green‐Screen Overuse

After the triumphant, practical‐effects mastery of Vikram (2022) and reuniting with director Mani Ratnam after nearly four decades, fans of three generations expected nothing less than visual cinematic fireworks. Instead, many set‐pieces — most glaringly Sakthivel’s pre-intermission showdown in Nepal — are undermined by crude green‐screen backdrops. Rather than immersive action, viewers get a surreal, almost cartoonish tableau that betrays the film’s serious tone.

4. Disconnected Musical Score

A.R. Rahman’s compositions remain among Indian cinema’s greatest assets, but here his songs feel shoehorned in and at odds with the drama on‐screen. The background score often swells or cuts abruptly, mismatching the narrative’s emotional beats. And though the standalone tracks (“Mutha Mazhai” included) had chart‐topping potential, they rarely integrate organically into the film’s flow.

5. Underwhelming Antagonist Arc

Another huge disappointment is from Silambarasan TR; he played Ethi in Chekka Chivantha Vaanam (2018) has more reasons to turn against his own brothers than Amaran turning against Sakthivel in Thug Life (2025). His efforts including growing long hair does not elevate nothing in the film. His arc, betrayal against his father, taking over the clan lack the narrative weight needed to justify the family‐saga stakes, making his eventual showdown feel perfunctory.

Finally:

Thug Life (2025) pinballs between high ambitions — a generational reunion of legends, a father–son epic, jaw-dropping stunts — and disappointing execution: erratic pacing, uneven sub genres, overused digital effects, underused cast and a score that never quite syncs.

It is easy to compare the characters of Thug Life (2025) with Chekka Chivantha Vaanam (2018). Watching Thug Life will make us think, do we still want to watch new films rather than revisiting old classics, as we have enough of films already to watch for the rest of our lives?

In Short:

Thug Life (2025) had the potential to be a new classic; instead, it feels like a cautionary tale of dangling promise.