“Theory will only take you so far” this quote from the film gives me an idea that it is a fusion of one’s limited knowledge and boundless curiosity.

Rewatching Oppenheimer, I discovered what I had missed the first time—blame it on the long narrative or my own ignorance, it was not easy to digest what I consumed in my first time viewing of Oppenheimer in 2023. The film, based on the book American Prometheus, is not just about the man who invented atomic bomb—it’s about his internal contradictions, his insatiable thirst, and the cost of his ambitions—I see this as his “curiosity”.

Oppenheimer is undoubtedly one of history’s most complex—and perhaps controversial—figures. But his brilliance and his relentless curiosity knew no bounds; those sleepless nights in the prologue, during his learning phrase, didn’t know what his curiosity was about to leash when it would get the whole flesh and bones.

It is shown to us that Oppenheimer was a fast learner. He could master a new language in weeks just to deliver a technical and scientific speech in it to native speakers—apart from attracting others with his impressive scientific brain, he continued to impress his peers with other skills too. I may not share his level of intellectual prowess, but I was able to recognise his drive for the innovation, the same way General Leslie Groves did in the movie, played by Matt Damon.

Curiosity as a Double-Edged Sword

Maybe it is because a historical and scientific drama about an invention—almost all the characters beyond having their own interest, all seek some sort of “curiosity”. The curiosity in exploring what Oppenheimer is doing in Los Alamos; whether or not Oppenheimer was being a spy to American rival nations; how was his relationship with Jean and how she died. One after the other, these curious questions made the movie more gripping and engaging even for a rewatch and made me think more about “curiosity” in general.

I didn’t just learn passion or innovation can be both inspiring and destructive from Oppenheimer (2023), but innovation is inspiringly destructive itself. We pursue our creative ambitions with such intensity that they consume us one day. Oppenheimer’s inability to rest, his compulsion to push forward, is something beyond my understanding. There are nights when my ideas won’t let me sleep—when the desire to create overrides everything else. But where does that pursuit lead? When does ambition become self-destructive? When does a creator become the villain for his own innovation and to himself? Even the greatest scientific minds the Earth ever seen may not answer to this.

Strauss, Teller, and the Cost of Curiosity

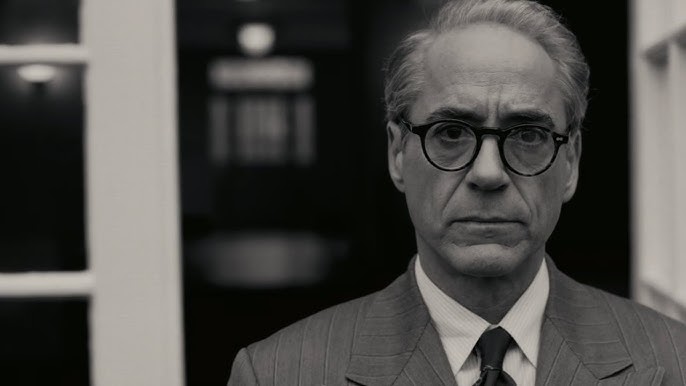

While Oppenheimer is dealing with his scientific curiosity, Lewis Strauss is seeking his own downfall, perhaps his self-destruction out of his own curiosity. Almost, during the testing, as soon as the bomb detonated, the audience’s expectations in the Cinemas would have left their bodies too—purpose of most of the audience might have been fulfilled seeing the bomb goes off. But the film still had one fresher act to unfold—the cold war between Strauss and Oppenheimer.

The insult in front of audience is a just a fuel to Strauss’s pre-existing curiosity; the curiosity of how scientific minds work—especially for a non-technical person that would make them feel inferior. His obsession with uncovering Oppenheimer’s private conversation with Einstein—his unrelenting curiosity that they might have talked about him—leads to face the trial that goes out of his control; his calculated moves now become subject to question—Strauss bomb didn’t go off like the one Oppenheimer built for three years.

While we talk about obsession over a subject—I still want to address the interest and obsession as a “curiosity”; as all part of one large spectrum. The movie showed the lack of curiosity could also play a role as a factor which would help in a character’s defeat. It was Edward Teller’s curiosity about hydrogen bomb.

In the film, it is shown to us that all the scientists involved in the Manhattan project including Oppenheimer barely showed any interest in Teller’s idea—even ridiculed his vision. The amalgamation of embarrassment and curiosity of a person has the potential to steer towards a man’s ruination—sounds familiar?

Like Strauss, Teller’s impact on Oppenheimer is huge. At some point, Oppenheimer agrees to meet every week an hour to discuss about Teller’s recent finding about Hydrogen bomb—Not that Oppenheimer was interested in it but he needed Teller to bring his creation into this world, not Teller’s. This Oppenheimer’s disinterest in Teller’s curiosity cost him a valuable ally—someone who could have defended him during the security clearance hearings. Had Teller’s curiosity acknowledged, he might have spoken in Oppenheimer’s favour, helping to clear his security clearance and secure the recognition and accolades he deserved for his contributions to his country—after all Oppenheimer’s innovations are only meant to save America, make America proud and stronger; instead of getting bad reputation among his fellow Americans.

What Ifs and the Nature of Curiosity

Curiosity is not just about discovery—it also fuels betrayal. The hypothetical questions are always unavoidable and unreasonable to even think about, but this comes from “my curiosity” to think and couldn’t stop pondering about the consequences of a lot of “what ifs”.

What if Einstein had stopped and spoken to Strauss instead of walking past him? What if the scientific community had embraced Teller’s ideas, altering the course of history? The film suggests that circumstances, more than inherent evil, push individuals toward choices they might not have otherwise made. Strauss’s obsession, Teller’s resentment, and Oppenheimer’s blind spots all stem from their own curiosities, and ultimately, their downfalls are shaped by them.

Beyond the external betrayals and conflicts, Oppenheimer delves into the internal cost of curiosity. The film presents a man haunted by the consequences of his creation, a mind unravelling under the weight of guilt and recognition. His famous words, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” take on a new meaning as he realises the lasting impact of his own work. It is not just about the immediate destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but the precedent he set for future wars. The arms race begins, the Cold War looms, and Oppenheimer is left staring into the abyss of what he has unleashed.

Conclusion: The Inevitable Cycle of Creation and Destruction

His moral struggles, and his ultimate isolation from the community paint a picture of a man who could no longer control the consequences of his own curiosity. Once his sleepless nights for the “curiosity” to discovering a new world leads him to an innovation that man-kind ever seen; and in the end, the same curiosity gives him sleepless nights of resentments and guilt.

Oppenheimer’s story is one of contradictions: a man who sought knowledge but unleashed destruction, a patriot who was cast aside by his own country. The film illustrates how curiosity, when left unchecked, goes out of control, can be both inspiring and ruinous. The same force that drives us to create can also lead to our undoing. In the end, self-destruction is not just a consequence of ambition—it is an inevitable creation of mankind itself, starts from “curiosity”.

Leave a comment